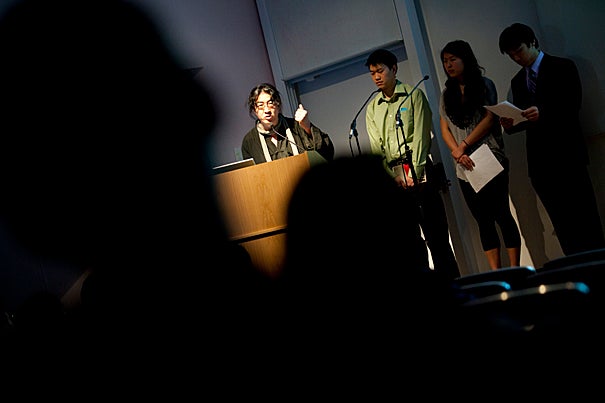

Editors of three literary magazines banned or at risk in their home countries talk about the hard work of creative writing in oppressive regimes. “The Living Magazine” event that takes place in the Sackler Museum auditorium features a panel of writers from China, Iran, and Burma. Bei Ling (left) speaks from the podium.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

The Living Magazine

World writers find their voice at Harvard

During the Iran-Iraq War, Shahriar Mandanipour wrote short stories under fire. He would compose one line at a time between exploding mortar rounds.

Back in Tehran after the war, Mandanipour started editing Thursday Evening, a literary journal. He came under fire again, this time from his own government. Censors combed through the essays and poems slated for publication. They feared that one might be a mortar round of another kind that scattered new ideas like shrapnel.

The journal was banned years ago, after surviving censors for eight-and-a-half years, and Mandanipour, now an acclaimed novelist, is an associate in Harvard’s Department of English.

Thursday Evening came briefly to life again last week (April 14) during “The Living Magazine,” a literary event that featured writing from banned or at-risk publications in Iran, China, and Burma.

Even Cambridge audiences, like the one 100-strong in the auditorium at Sackler Museum, need reminding: In many countries in the thrall of oppressive regimes, writing is still a dangerous pursuit.

Reading their work were writers who had once suffered arrest and imprisonment. One of them, Chinese poet Bei Ling, edited the literary magazine Tendency. In 2000, print copies were seized by the Beijing Office of Public Security, and Ling was arrested.

“I was guilty of a crime that no civilized country would count as a criminal act,” he said, “the illegal publication of a literary journal.”

Ling paraphrased what writer Susan Sontag wrote about the incident, “that my crime should be called: bringing ideas to China.”

Mandanipour avoided arrest but lived in fear for his life, he said, and “fear for my unwritten stories.”

During those postwar days, editors, writers, and even translators were being killed for their creative work. “Gloom and fear seeped into our lives,” said Mandanipour, author of the 2009 novel “Censoring an Iranian Love Story.” “No one could guess who the next person would be.”

Other glimpses of gloom and fear came up in “The Living Magazine,” which was conceived by Jane Unrue, who teaches in the Harvard College Writing Program and who is a member of the Harvard chapter of the Scholars at Risk Committee. “The Living Magazine” is not bound or numbered or even a virtual publication, she said. It is a “dream space” that imagines worldwide freedom for writers.

Avant-garde poet Meng Lang, a veteran of China’s underground scene since the late ’70s, put literary print magazines in the tradition of the “little magazines” of the 1920s and beyond — as well as in the tradition of furtive samizdat literature in the Soviet Union’s Iron Curtain.

China these days, he said, is no longer the Bamboo Curtain, but a “Silk Curtain … hiding China’s last brazenness, or cowardice, from the powerful winds of freedom.”

It is joined now by pressures from the “Gold Curtain,” the race for profits not only in China but around the world.

Lang’s own beleaguered publications started with the 60-copy MN01 in 1981. Now he is managing editor of the online literary journal Freedom to Write. “I will not give up,” said Lang. “We are the nurturers and protectors of living magazines.”

“The Living Magazine” was the second annual literary event in Harvard’s Visiting Writers Series, inaugurated by Unrue last year. It drew back the curtain on poems and essays that were heartfelt and brilliant, with many of them the work of imprisoned authors.

“Help keep these voices heard,” said novelist and editor Nicholas Jose, visiting chair of Australian studies at Harvard. He was one of the readers — many of them Harvard undergraduates — who delivered passages from the imprisoned, the exiled, and the dead.

Jose read the words of Liu Xiaobo, a Chinese human rights activist in prison for 12 more years. He was a signatory to Charter 08, a 2008 manifesto marking the 60th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights adopted by the United Nations. Xiaobo only twice spoke in a public forum in his native country, said Jose, “and both of those times have been in court.” His crimes, he added, were “both crimes of expression.”

Jose read from one of the court statements. “I have no enemies and no hated,” said Xiaobo. “For hatred is corrosive of a person’s wisdom and conscience. The mentality of enmity can poison a nation’s spirit.”

Facing prison, the writer remained full of optimism that China would one day embrace human rights and the rule of law. “I hope,” said Xiaobo, “to be the last victim of China’s endless literary inquisition.”

There was a reading from the Burmese poet Yekkha, arrested for his participation in the 1988 democracy movement. He spent 20 years in prison. A fragment, read by Ben Biran ’13, says:

I hear the bells from the churches

I don’t see those

They don’t see me.

Young-jun Lee, a fellow at Harvard’s Korea Institute, read from the work of two poets, one from the south and the other from the north. Both felt the sting of a divided country.

North Korean poet O Yong-jae is known for “Oh, My Mother,” written in 1990 when he heard his mother was still alive in South Korea — 40 years after leaving her during the Korean War. “A sun suddenly rises in the middle of a black night,” he wrote.

In South Korea, the ironic “Long Live Kim Il Sung” could not be published during the lifetime of poet Kim Suyong (1921-1968), a writer so direct about advocating for a free literature that even some of his friends regarded him as dangerous.

Former Russian journalist Maria Yulikova provided a reminder that members of the press can face the same dangers as poets and novelists for simply writing truths in another way. “You might want to use your pen name,” she said of journalists in her native Russia, “just to be safe.”

Rumbidzai Mushavi ’12 read snippets from Chenjerai Hove’s “Letter to Mother,” a voice that wove through the event three times.

Driven from his native Zimbabwe by death threats, Hove, who is a poet, essayist, novelist, and dramatist, has been in exile since 2001.

It was a reminder that imprisonment can also mean having to live away from home. He wrote, “Every sunset reminds me: I am in another land.”

Mandanipour, who is also a visiting writer at Boston College, spoke of exile’s pain too. “You shut the doors and windows of your house to others,” he said. “You get angry, and anger keeps you on your feet.”

Hove cut to the heart of the matter for oppressed writers, struggling in exile or at home. He told his illiterate mother, “You can’t read, and I — oh, the hopelessness — I can’t write.”

With hopelessness sometimes comes guilt. Ling recalled a trip to the printer in 2000, on a mission to make two deletions from his magazine: the name of a Tiananmen Square activist and the word “anti-communist.” (He was arrested anyway.) “I was committing an act of self-censorship,” said Ling, “just as all editors and writers in China still do today.”

Mandanipour recalled many nights of pacing at his office, wondering which voice to cut out of Thursday Evening.

On one hand, he said, there was his personal style as a literary editor: “My role was never to change or delete a single word in a text.”

On the other hand, he ended up snipping out some controversial writers. “I sometimes think I should have published that good poem or story,” said Mandanipour, “and not publishing them remains a shame in my life.”

Of the writers and editors speaking at “The Living Magazine,” only one worked for a publication still afloat: Burmese writer and Radcliffe Fellow Ma Thida, editor of Teen magazine in Rangoon. None of the contents are explicitly political.

“I don’t want to lead the next generation,” said Thida of her audience, who live largely outside the grasp of the Internet. “I just want to deal with them, to hear their voices.”

Voices were the point of the session, many of them little-known, all of them strained through pain and guilt. But the dream survives.

“Waiting for the daytime sun … I sing and play a deep melody in these bright years,” read Chinese poet Ar Zhong from his “Darkness, the Theme of my Life.” “Morning appears in my dreams.”

Ling read from his poem “For Dreams to Linger, and for Time,” a paean to the power that print still has in countries where censors rule.

“Wishes,” one line reads, “are pressed into a paper surface.”

Providing support for “The Living Magazine” were the Humanities Center at Harvard, the Harvard College Writing Program, the Office of Undergraduate Education, the Office for the Arts at Harvard, and the Undergraduate Council.